The brewing landscape is more competitive than ever and having a direct route to market remains one integral way to provide the consumer with fresh beer while driving revenues straight back into your brewery. It was an approach Jean-François Gravel and Stéphane Ostiguy took when they opened Dieu du Ciel! in 1998 and more than twenty years on, it’s safe to say it was the right call.

You should challenge the drinker and strive to make the best beer possible. I see setups with 20 taps and 19 of those are New England IPAs. Is that all people really want? Because if they tire of that, you’re in danger. As brewers, we should always be looking to push the boundaries,” explains Jean-François Gravel co-founder of Montréal’s Dieu du Ciel!.

And for a brewery with no less than 346 beers listed with online ratings directory RateBeer, a failure to explore the spectrum of beer styles isn’t an accusation you can throw at the Quebec-based business.

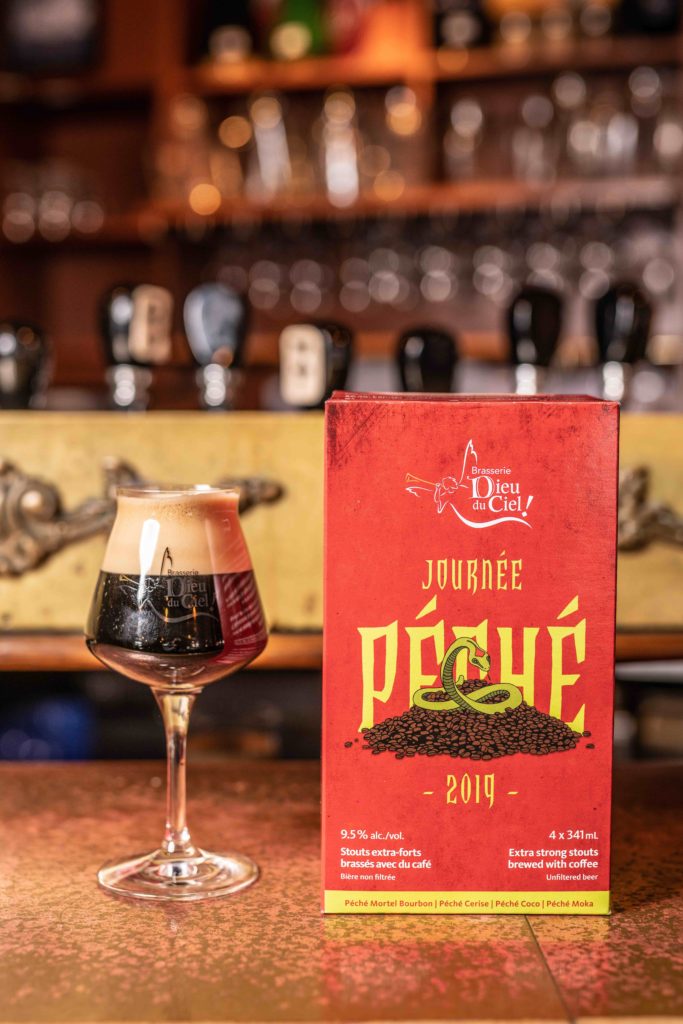

Beers have come in at 3.5% ABV right up to 11.6%, and they’re only the ones listed on the aforementioned portal. For every Péché Mortel, the venerable 9.5% Imperial Stout that has admirers across the globe, you have wheat beer Rosée d’Hibiscus, Moralité, an IPA collaboration with The Alchemist, or Québec Draken an 8.5% Doppelbock.

Gravel and co-founder Stéphane Ostiguy have always brewed the beers they want to make. It just so happens that drinkers across the world want to come along for the ride. And quite the ride it’s been during the 20 years since the duo opened up their Montréal brewpub back in September 1998.

“People always tell me ‘Wow’ how time has flown but I think, working each day you certainly don’t feel that way! We started out with the aim of sticking around for many years. But did I expect to be here more than two decades on? No way!” exclaims Gravel.

Though Dieu du Ciel arrived kicking into the Montréal beer scene in 1998, with 300 people in attendance for its opening party, Gravel’s passion for beer was seven years in the making at that point.

A keen home brewer, Gravel would soon meet Ostiguy when the duo were studying Microbiology at the Armand-Frappier Institute in Laval, Quebec. Ostiguy would prove to be a willing lab rat for Gravel’s fine home brew creations, a bond was formed and the first chapter of Dieu du Ciel was written.

From 1995, time was spent imbibing at bars such as Montréal’s Cheval Blanc brewpub and in 1997, the duo happened upon a promising location at 29 Laurier Avenue West for their own operation. For the best part of a year, they worked around the clock in order to prepare the brewpub for opening. Walls were torn down, part of the floor was ripped apart and the basement was dug out by hand and spade in order to install the brewing equipment.

“During the mid 1990s, most breweries in Quebec were having a hard time, or closing altogether. There was a broader focus on breweries distributing their beer but we wanted the freedom to brew what we wanted and an easier way to sell it, so a brewpub operation made complete sense,” explains Gravel.

The duo opted for a location in central Montréal to give themselves the best possible chance of making the business a success.

“Things have changed a lot. When we started out, the population wasn’t an issue, but reaching them and grabbing their attention, was,” says Gravel. “There was no social media so you had to rely on word out mouth and local publications. Beer was a much harder sell than wine, for instance. “

He adds: “There were breweries and bars in the big cities but travel a short while out and that changed a great deal, and good beer was harder to find. Even if there was an appetite for it.

“But that’s no longer the case. Most small cities have a brewpub, a brewery, and stores to buy them. There are different drivers behind this growth. Previously people dreamt of having a brewery and making beer. Now there’s a lot of interest in the business opportunity it presents. It’s an interesting mix.”

The early days of Dieu du Ciel would comprise six-day weeks. The first part of the day involved brewing, cleaning and office responsibilities before the brewpub opened to thirsty drinkers that would be served from 3pm all the way into the early hours. This continued for at least half a year before they relented and hired help for the bar.

Local appetite for the outfit’s beers started, and continued, unabated. An annual capacity to brew 800 hectolitres a year would soon be outstripped.

Beers that Gravel and Ostiguy expected to resonate with drinkers did just that, while other more ambitious creations would follow a similar path. One such beer was Rosée d’Hibiscus, which remains a hit and one that came from Gravel experimenting with making Hibiscus juice in his spare time.

“It was tart, floral, fruity. Maybe it would go well in a wheat beer, I thought. The beer would be pink and could show off the Hibiscus. At worst I thought we could bring it to a beer festival and gauge what people thought,” he explains. “People loved it! It travels well, complements food and it’s not too bitter.”

The idea of such a beer is at the very core of Dieu du Ciel’s ethos, its missions statement. The desire for the new and to challenge existing preconceptions on what beer can be. It is, perhaps, no surprise to see ingredients such as Hibiscus now common place in the brewing landscape.

“As a brewer you want to explore new creations, new experiences,” he says. “But it is important to perfect these, and evolution is key. I like to brew new ideas and the 5HL batches at the brewpub allow for that. It enables risk but it is valuable market research, too. You might see a consumer have one glass of a new beer, and that’s it. But a following night they’ll come in and order the same beer again. That’s reassuring, and rewarding!”

In the first years of the new millennium, the desire for the brewery’s beers led the duo, like many since them, to the point where expansion was a necessity if they wanted to fulfil market demand, and capitalise on the growth opportunity in front of them.

With the help of Luc Boivin, an electro-mechanic with impressive home-brewing experience, and Isabelle Charbonneau, an expert in sales, management and marketing, the team formed what would be known Dieu du Ciel Microbrewery, a new location where the products will be bottled and distributed.

They settled on Villemure Street in St-Jerome, turning a vacant supermarket in the heart of St-Jerome’s downtown area, to a new production site. An on-site tasting room was added in August 2007 with the first beers produced at the facility served the following January. Boivin would then leave to the business to pursue his own brewing journey.

Dieu du Ciel has changed a great deal since its inception in the late 1990s, but so has the industry around it. A team of 80 are employed across both sites while the production facility can output up to 13,000HL per annum. The Montréal’ brewpub continues to afford the brewery a direct sales channel for its beers with 100% of everything brewed on site, sold on site.

In contrast, around 10% of beer brewed in St-Jerome is sold over the bar. Much of what is produced in St-Jerome is bottled for distribution to Canada, North America and also further afield to countries such as France, Spain and Italy.

In the wider landscape, the industry is more competitive than it was back in 1998, while the advent of social media affords breweries the type of exposure not available to Gravel and Ostiguy 20 years ago.

“Sure, social media is a great tool but there are so many beers out there, it’s also harder to grab people’s attention,” says Gravel. “The problem is getting that level of repeat custom and building a long-lasting relationship with the consumer.”

He adds: “With many new breweries, I see them pushing out lots of new beers. This is fine but you must also concentrate on establishing a base and repeatability. There will also be an appetite for novelty but there are a lot of beers going out that aren’t up to scratch.

“If people spend hard-earned money on a beer that is below-par, then that can have a lasting negative impact. People want great beer, beer that’s reliable. That shouldn’t be too much to ask.”

Just don’t ask Gravel what the next big thing is beer is, because even he doesn’t know.

“I just create beers and hope people like them. The times I’ve tried to conform, it’s not really worked,” he smiles. “But thankfully people like what we do. For a long time sour beers were supposed to dominant but that never really happened. Now it’s lager. To be honest I think the desire for lager is brewer-driven as we all love lager and want it to catch on!”

Observing trends isn’t of interest to Gravel, though. He and Ostiguy are more interested in making great beer that people enjoy and supporting the ever-growing team that work across both of its sites.

“Our first team Christmas party was a few of us sitting around a table. We didn’t expect to be in this position, but here we are! We’ve grown because we’re obsessed with quality. The future of beer should be about quality. If you focus on that, you’re likely to fulfil your expectations and those of the drinker. And surely that’s what’s important.”