There is a huge love for craft beer in West Michigan but hop farmers are worried that the trend is moving downwards, leaving the farmers worried that they’ll be left behind.

The pandemic shutdowns played a role, but one local farmer says it was just one of several factors.

“It was kind of the nail in the coffin, I guess,” Nicole Johnson said of the mandated closures during the pandemic.

Johnson and her family run Egypt Valley Hop Yards in Ada, east of Grand Rapids. The family established hops in the ground in 2013, when the craft beer industry was in full swing and hops were selling at a premium price. But thanks to the pandemic, they have decided to liquidate.

“We decided to grow hops because (at that time) growing hops was a really good business. People were doing pretty well to support all these breweries,” Johnson said. “And if all of these (breweries) were going to be opening, we’re going to need more hops. And so I think a lot of people, there was a lot of, I guess, hope in the industry.”

Hops are a commitment to anyone who decides they want to proceed with this investment. Plants take three years before they are mature enough to provide a full harvest of cones. When Egypt Valley Hop Yards put its first plants in the ground, the farmers were looking at 2016 and 2017 as their first big harvests. But when those seasons came around, the hops market was already full with other suppliers and selling the product for a profitable price became much harder.

“Fifteen years ago, when (a lot of farmers) were starting, they were getting $15, $20 bucks a pound for hops because there was a shortage. That’s not the case anymore,” said Rob Sirrine, an agriculture expert with the Michigan State University Extension.

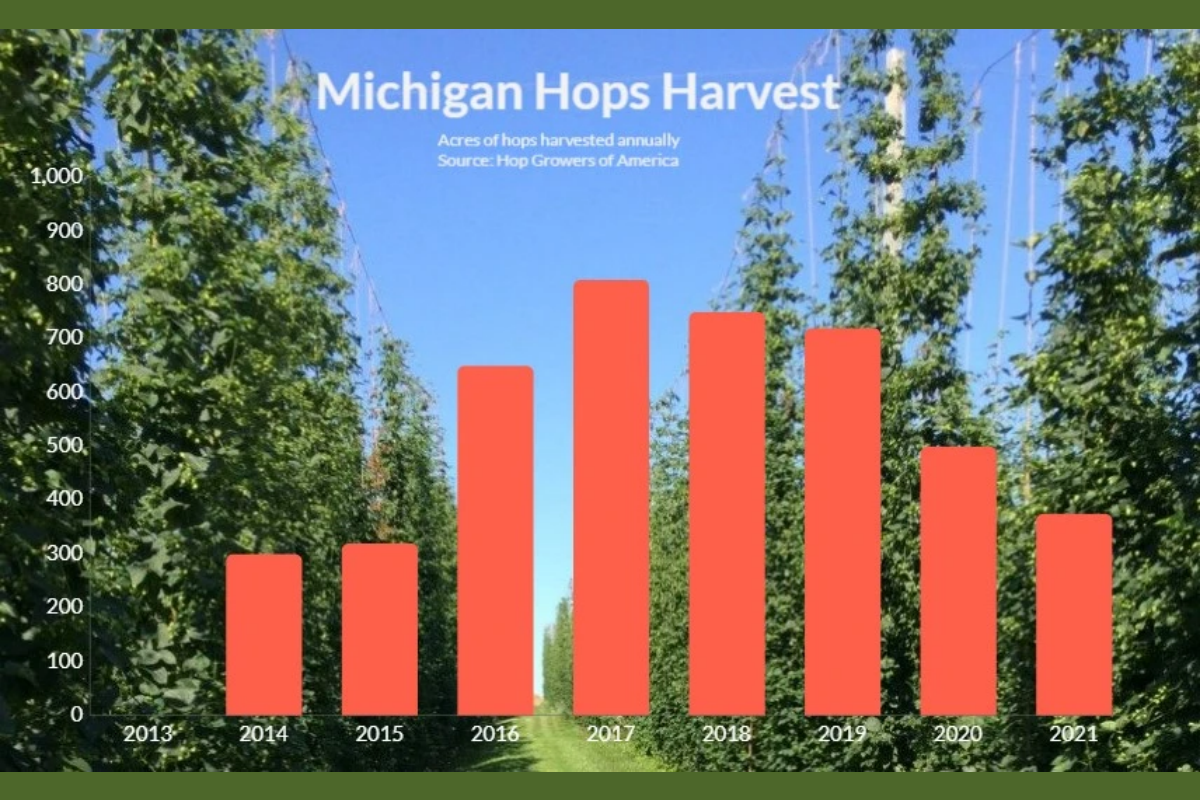

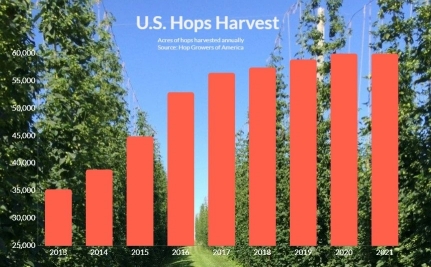

According to the Hop Growers of America, in 2012, about 29,000 acres of hops were harvested across the country, almost all of it in Washington, Oregon and Idaho. Michigan had no hops harvest to report but reported 300 acres of hops harvest in 2013. Michigan’s hop harvest peaked in 2017 at 810 acres, but at that point, the hop harvest nationwide had nearly doubled to 55,700 acres.

According to the Hop Growers of America, in 2012, about 29,000 acres of hops were harvested across the country, almost all of it in Washington, Oregon and Idaho. Michigan had no hops harvest to report but reported 300 acres of hops harvest in 2013. Michigan’s hop harvest peaked in 2017 at 810 acres, but at that point, the hop harvest nationwide had nearly doubled to 55,700 acres.

“We have two main varieties that are still in our freezer at this point,” Johnson said. “And we’re actually in the process of maybe setting a huge sale. I mean, we’re talking like $4 a pound when our business model is hoping for above $10 a pound.”

Mary Dieleman, one of the founders of Pure Mitten Hops, told News 8 that they had to destroy much of their harvest last year because they ran out of storage space and needed to make room for the next one.

“It was already a struggle to sell hops because there were so many hats and so many options, and then COVID hit and our main customer is going to be your smaller brewer,” Johnson said.

“We saw less people buying hops because there just wasn’t as much production.”

The good news is according to the National Beer Wholesalers Association, beer manufacturing is back up to its pre-pandemic numbers.

“If we want to take the spirit of distribution, we got to bring those numbers down because distribution, if you really do the numbers, if you go to the conferences and you listen to the distribution panels, it’s a very, very fine line of where those margins are,” said Mike Moran, the president of MI Local Hops. “A lot of those breweries that are in the 1,000-barrel to 10,000-barrel range. They don’t make that much money in distribution. And once they get the distribution, it’s extremely competitive.”

“I think what we really need is for each farm (to have) three or five brewery partners,” Johnson said. “If there were brewers that would just commit to buying hops from one farm, like say they use 500 or 1,000 pounds of hops a year. We grow maybe 3,000 pounds a year. We had one really solid partner, a couple other contracts. And then we sold a ton on Lupulin Exchange, which is like an online marketplace for hops.”

Johnson and the team behind Egypt Valley Hop Yards say they are proud of their work, especially the team’s Chinook hops harvest in 2019 and 2020, which were named second-best in the state by the Hops Growers of Michigan.

“We grew some great hops,” Johnson said. “We had so much fun doing it and we learned a lot and we’re really proud of the hops that we grew.”

“I hope that hop industry does well,” Johnson said. “And I think there’s a lot of really good people who, I mean, we’re all doing the best that we can and I’m sure breweries are, too. It’s a hard time.”

Infographic by Matt Jaworowski, Photo by Nicole Johnson