“After you’ve done a beer, you can age it in a barrel. Sometimes, craft brewers use a barrel that’s got a yeast called Brettanomyces in it,” said Chris Eskiw, an associate professor in Agriculture and Bioresources at the University of Saskatchewan.

“It (Brettanomyces) gives beer a really funky and earthy flavour…. The description in the handbook of flavours is barn floor or horse blanket.”

Why someone would want to drink a pint of horse blanket or barn floor is hard to explain.

But Eskiw and other beer experts do know what’s responsible for all the flavours on the wheel, even cheesy/sweaty socks. It’s the yeast!

“Most people think that yeast is yeast is yeast,” said Eskiw.

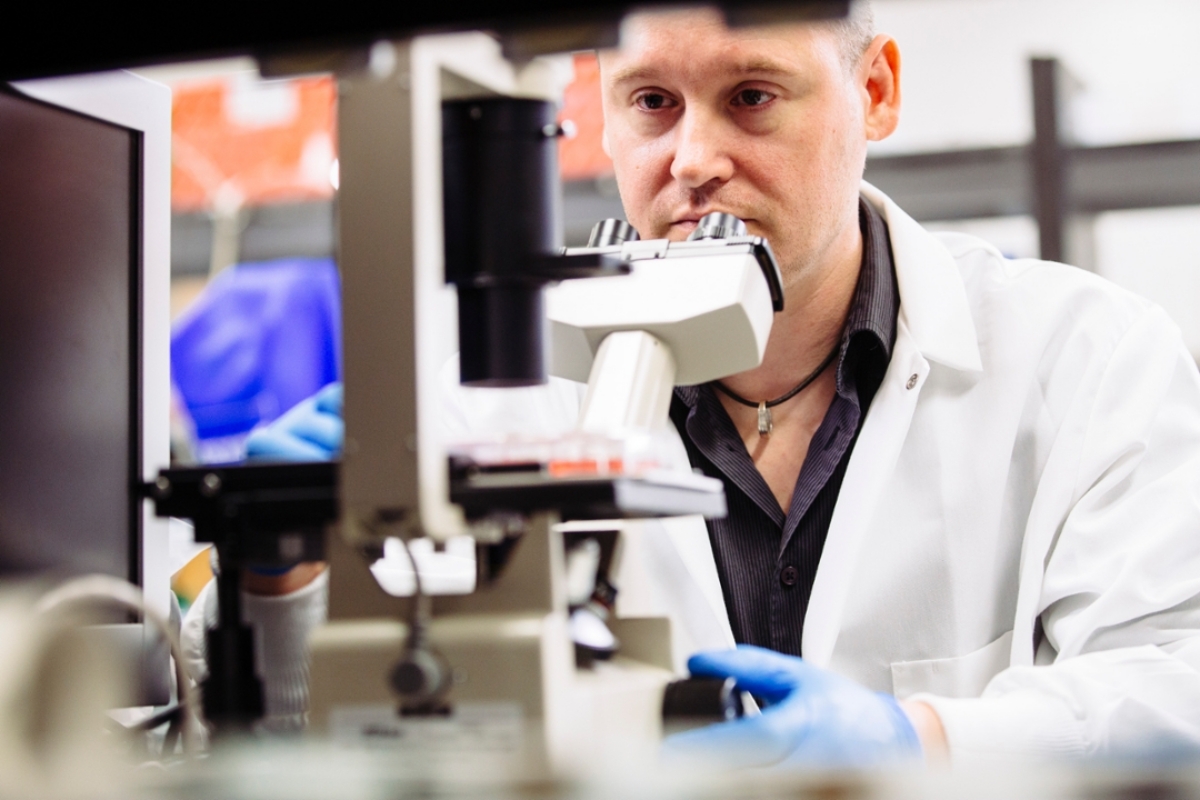

Chris Eskiw associate professor in the Department of Food and Bioproduct Science at the University of Saskatchewan analyses yeast colonies on an agar plate to make sure they are pure and free from contaminating organisms. | William DeKay photo

“There are differences in the genetic (makeup) of these yeasts that allow them to do different jobs, under different conditions,” he said. “Like any good recipe you need good quality ingredients. And the malt certainly provides that material. But the yeast takes that raw material and converts them into many of the flavours… that we enjoy so much. The yeast are the little factories that give those beers their diversity.”

Eskiw and his University of Saskatchewan coworkers want to know the answer to it.

Eskiw received a $120,000 grant from the Agricultural Development Fund in Saskatchewan this year to investigate the connection between yeast genes and beer types.

Currently, most of our understanding of yeast is based largely on trial and error.

Over decades or centuries, brewers experimented with many kinds of yeast until they discovered one that was effective for a particular kind of beer, such as a pilsner. They continued to utilise the yeast since it gave the pilsner the flavour they were looking for.

“For example, Carling and Carlsberg out of Europe, they’re going to have their favourite house strains (of yeast) that perform really well with the recipe that they’re using,” Eskiw said.

“They’re not really going to share information on the genetics of that yeast… with other companies.”

At least for Canadian craft brewers and home brewers, Eskiw wants to increase the transparency of the relationship between yeast genetics and beer quality.

To determine the connection between the yeast gene and flavour, he has been researching the genetic composition of several yeast strains. A manual that brewers may use to choose yeast that is appropriate for their requirements will be published, according to the proposal.

In addition to his primary area of expertise in human lifespan and food, Eskiw is now conducting research on yeast.

He investigates how a person’s health is impacted by the link between their genetic make-up and the foods they consume.

As part of the research, Eskiw’s PhD student is collaborating with the 21st Street Brewery at the Hotel Senator in Saskatoon to examine how the yeast behaves in brewing operations of 600 and 1,300 litres.